- INTRODUCTION

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) released the draft of ‘The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022’ (DPDP Bill/ 2022 Bill) afresh on 18th November, 2022.[1] The earlier version of the draft Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (2019 Bill) and subsequent draft Data Protection Bill 2021 (2021 Bill) as submitted by the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) was withdrawn by MeitY recently in August, 2022. After a brief hiatus, the Government rolled out the present draft Bill with the intent to present a simple and easily comprehensible draft, both in terms of understanding and future compliances.[2]

The “Digital Nagriks” (Indian citizenry, as referred to in the draft Bill) are a significant participant in digital innovation. To this end, the Bill has emphasized that “Data in general and Personal Data in specific are at the core of this fast-growing Digital Economy and eco-system of digital products, services and intermediation” and hence, a nuanced set of framework and rules need to be enacted to facilitate a safe growth environment and regulate responsible usage of data.

A. Highlights of the Draft Bill

A few things which vividly stand out in the draft Bill are; firstly, the usage of ‘illustrations’ to explain the provisions of law, as we typically read in the Penal laws in India or the Indian Contract Act, 1872. Secondly, the draft Bill has significantly reduced the number of Sections/ provisions as compared to what we had seen in the earlier versions of the Bill. Thirdly, in contrast to the earlier versions of the draft Bill, the DPDP Bill takes a principle-based approach wherein, governing privacy principles have been laid down and much has been left to be regulated through delegated legislation to address the dynamic demands of technology regulation. Fourthly, the DPDP Bill has done away with the differential approach and categorisation of personal data into sensitive, personal, and critical data. It is also in significant departure from the extant rules, i.e. Information Technology (Reasonable security practices and procedures and sensitive personal data or information) Rules, 2011 (SPDI Rules). Fifthly, it can be the first law in India to use ‘her/she’ pronouns for an individual, irrespective of gender. Other critical areas and changes have been discussed in the succeeding parts of the article.

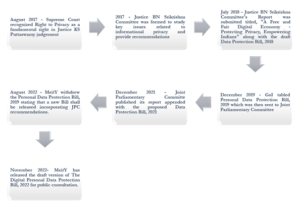

B. Timeline of the Privacy Bill in India

The MeitY has informed that feedback on the draft bill may be submitted by 17th December, 2022.[3] The chart below represents the timeline of the Privacy law-making journey so far in India.

2. KEY ASPECTS OF THE DPDP BILL

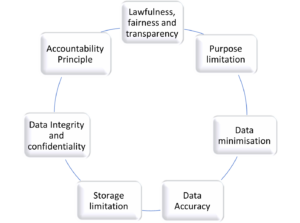

The draft 2022 Bill induces a balancing effect to bring the Rights of data principals in tandem with business viability and ease of compliance for data fiduciaries and data processors. The draft Bill has been formulated on the touchstone of the following seven key privacy principles.

Privacy principles incorporated under the draft DPDP Bill

In the ensuing parts, we shall discuss the various facets of the DPDP Bill and put them into perspective from the enforcement standpoint. The analysis below shall also consider what has changed in comparison to the 2021 Bill and the extant SPDI Rules.

A. A Brand-New Name

This is the fourth iteration of the draft data protection law and continuing with the trend, the DPDB Bill comes with an alteration in the name, yet again. The usage of the word ‘Digital’ and emphasis on the protection of ‘Digital Nagriks’ has positioned the intention of the government on right track and highlighted its streamlined focus. The Preamble of the Bill signifies that the purpose of this law is “to provide for the processing of digital personal data in a manner that recognizes both the right of individuals to protect their personal data and the need to process personal data for lawful purposes.”

The Bill focuses only on regulating the usage of digital personal data (without any further classification of data) and leaves behind the erstwhile thought to squeeze the regulation of non-personal data and social media intermediaries all into one law. The present draft addresses the common concerns of the stakeholders agitated in reference to the 2021 Bill.

B. Roadmap for implementation

Unlike its predecessor, the DPDP Bill does not give a timeline for the implementation of various provisions of the Bill, if enacted into law. It simply states that “it shall come into force on such date as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. Different dates may be appointed for different provisions of this Act.”[4]

However, the 2021 Bill while adopting the lines of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union provided for an eighteen months implementation period. Such indication in the law gives stakeholders a timeline for groundwork related to compliance and putting in place the processes and systems.

C. Focused Scope and Applicability

In contrast to the earlier versions and the extant Rules, the 2022 Bill does away with the categorization of personal data into any sub-sets (viz. sensitive or critical data) and uniformly applies to digital ‘personal data[5]’. It also excludes non-personal data from its ambit.

The intra-territorial applicability of the Bill is limited to personal data collected online and personal data that is collected offline and then digitised.[6] It is pertinent to note that as a silver lining, the outsourcing and BPO industry based in India has got certain exemptions from onerous obligations related to the processing of personal data of ‘Data Principals’[7] not within the territory of India (foreign nationals), which is processed pursuant to any contract entered into with any person outside the territory of India.[8]

The extra-territorial application of the Bill is akin to the previous versions, i.e., related to the processing of digital Personal Data outside India, if it is in connection with profiling of, or offering goods or services to Data Principals within India.[9]

However, while significantly departing from the 2021 version of the Bill, the DPDP Bill does not apply to non-automated[10] processing[11] of personal data, offline personal data, data for domestic or personal purposes and personal data about individuals contained in records that have been in existence for at least 100 years.[12] Furthermore, the bill does not make any reference to the regulation of anonymized data.

D. Itemized Notice requirement and ‘Consent’ mechanism’

The DPDP Bill raises the standard of the consent-taking mechanism in comparison with Rule 4 and Rule 5 of the existing SPDI Rules. Clause 6 of the 2022 Bill mandates for the Data Fiduciary to give to the Data Principal an “itemised notice” in clear and plain language (accessible in English and 22 different languages mentioned in the VIIIth Schedule of the Constitution of India) containing an individual list and description of each personal data sought to be collected by the Data Fiduciary and the purpose of processing of such personal data. The said provision shall also apply retrospectively and the data fiduciaries need to re-think the whole consent-taking process.

Furthermore, the consent should be freely given (which would ideally be tested on the standards of Section 14, Indian Contract Act, 1872), specific, informed, and unambiguous indication of the Data Principal’s wishes by which the Data Principal, by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of her personal data for the specified purpose.

Additionally, the 2022 Bill adopting the principles of Article 7(4) of GDPR and after fine-tuning it mandates that the performance of any contract already concluded between a Data Fiduciary and a Data Principal shall not be made conditional on the consent to the processing of any personal data not necessary for that purpose.[13] The noble insertion in this version of the Bill is that once the Data Principal withdraws her consent to the processing of personal data, the Data Fiduciary shall, within a reasonable time, cease and cause its Data Processors to cease processing of the personal data of such Data Principal.[14]

The role of ‘Consent Managers’ has been given more clarity in this newer version of the Data Protection Bill. They have been said to be an entity that is accountable to the Data Principal and acts on behalf of the Data Principal to give, manage, review or withdraw her consent to the Data Fiduciary. Every Consent Manager shall be registered with the Data Protection Board and other standards for them shall be specified through delegated legislation.[15]

It cannot be gainsaid that seeing the international development in privacy space and penalties being imposed on data fiduciaries; consent-taking mechanisms and notice requirements are of utmost importance under the 2022 Bill. Clause 7(9) of the Bill places the burden of proof on data fiduciaries to prove that notice was given and consent for the processing of personal data was taken in accordance with the law.

E. ‘Deemed Consent’ or re-christening the test of ‘legitimate interest’

The coinage of the term “Deemed Consent”[16] is in dereliction with the terms of common parlance used in international jurisdictions (eg. Article 6(1)(f), GDPR) as far as privacy law is concerned. However, when one reads the provision, the substance is similar to what is said to be ‘legitimate interest’ and ‘reasonable grounds’ for processing data. An indication for the same is provided in Clause 8(9) of the 2022 Bill, which gives power to the government to expand the scope of provision on being satisfied whether (a) the legitimate interests of the Data Fiduciary in processing for that purpose outweigh any adverse effect on the rights of the Data Principal; (b) any public interest in processing for that purpose; and (c) the reasonable expectations of the Data Principal having regard to the context of the processing.

Clause 8 enlists that deemed consent would be said to mean that either the Data Principal voluntarily provides her personal data or is reasonably expected to do so; or such processing of data is necessary for the performance of any lawful function, to address any medical situation or in the public interest (an inclusive list has been provided as to what would public interest mean). The provision when seen from a Data Fiduciary point of view would certainly bring a lot of ease to the whole consent-taking mechanism.

F. Significant Data Fiduciary

The criteria for the designation of an entity as ‘Significant Data Fiduciary’ (SDF) has changed under the 2022 Bill as compared to the 2021 Bill (Clause 26). Clause 11 of DPDP Bill adds that the determining criteria would now include the volume and sensitivity of personal data processed, risk of harm to the Data Principal; risk to electoral democracy among other factors. It has dropped the criteria of turnover of the entity as a determining factor as see n in the 2021 Bill.

However, the obligations of SDF by and large remains unchanged which includes carrying out periodic data audits (dropped the word ‘concurrent audit’ as used in the 2021 Bill) by independent data auditor, data protection impact assessments, appointing a data protection officer (DPO), among other compliances. The 2022 Bill mandates the DPO to be based in India and be responsible to the Board of directors of the SDF.

G. Cross-Border data transfer and data localization

In the 2021 Bill, there was much hullabaloo around the restrictive requirements of Data localization and the complex process of cross-border data transfers (Refer Clause 33 and 34 of the 2021 Bill). The government has tried to address the concerns of the industry in the 2022 Bill. Firstly, the obligations would apply universally to all kinds of digital personal data since there is no categorization anymore. Secondly, the Bill does not mention about data localization requirements. It simply states that after an assessment of such factors as it may consider necessary, the Central Government shall notify such countries or territories outside India to which a Data Fiduciary may transfer personal data, in accordance with such terms and conditions as may be specified.[17] Of course, the devil lies in the detail, but for now, the Government has decided to chart out the requirements through delegated legislation. The approach although looks quite similar to the adequacy requirements under the GDPR. The ‘Explanatory Note’ to the DPDP Bill also provides that the “Government recognizes the importance of cross-border data transfers for a globalised economy” and thus it is expected that no overly restrictive compliance obligation shall be enacted.

H. Data Protection Board and resolution of disputes

Clause 19 of the DPDP Bill prescribes for the establishment of a Data Protection Board (DPB) by the Central Government. Keeping in mind the purpose of the Bill and the technology era in which we thrive, the Bill says that the functions of the Board shall be digital by design.

The composition and eligibility requirements of the DPB have been left to be determined through delegated legislation. Clause 20 and 21 of th e 2022 Bill prescribes that the role of DPB as a regulator is to adjudicate on non-compliance of the provisions of the 2022 Bill (if enacted) on the receipt of a complaint or suo-moto and ensure the enforcement of provisions of the law. In contrast to the 2021 Bill wherein DPB was entrusted with the power to also issue regulations, the role of DPB is limited in the newer version and such power is vested in the Central government.

The DPB is said to have the powers of a Civil Court as provided in the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 for the purpose of the proceedings before it, and every order made by the DPB shall be enforced by it as if it were a decree made by a Civil Court. All appeals from the order of the DPB shall lie to the High Court and the DPB shall also have the power to review its own order subject to just reasons.

The 2022 Bill innovatively proposes the idea of alternative dispute resolution wherein if the DPB is of the opinion that any complaint may more appropriately be resolved by mediation or other process of dispute resolution, it may direct the concerned parties to attempt resolution through such process.[18]

I. Data Breach and reworked Penalty provisions

Under the 2022 Bill, a ‘personal data breach’ has been said to include both unauthorized processing and accidental disclosure, use, sharing, use, alteration, destruction of or loss of access to personal data, that compromises the confidentiality, integrity or availability of personal data.[19] The obligation of reporting data breaches has been extended to both Data Fiduciary and Data Processors.

Furthermore, under the 2022 Bill, criminal liability has been omitted and only monetary liability has been proposed which is governed by Schedule 1 of the 2022 Bill and is not contingent upon the relevant turnover of the entity, as seen in the earlier versions of the Bill. In so far as monetary penalties are concerned, if the non-compliance of the provisions of the 2022 Bill is adjudged to be significant by the DPB, it can impose penalty which can range from INR 10,000 to INR 250 Crore subject to mitigating factors mentioned in Clause 25(2) of the Bill. However, such financial penalty shall not exceed INR 500 Crore in each instance.

3. CONCLUSION

The draft Bill looks promising for the start of privacy law journey in India. It is simplified and ambitious as compared ot its previous versions. There is some obscurity in the Bill as the procedural aspects under the Bill have been left to be determined through delegated legislation. As we go along, nuances can be added and the Bill in the present structure gives scope for such incremental additions and changes. However, the demand for a simple and easy to understand data protection law is seen to be met in the current version of the draft Bill. As it is iterated in the ‘Explanatory Note’ to the DPDP Bill, “The Government has also considered our 1 trillion-dollar Digital Economy goals and the rapidly growing innovation and startup eco-system”. It is high time now that the government should act expeditiously and enact a data protection law. The interplay of technology, data, and law evidence that the start-up ecosystem in the country is really on the rise, thus the legal & policy instruments must ensure that business efficiency, sovereign interests and citizens’ rights have balancing effect.

[1] Available here: https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/The%20Digital%20Personal%20Data%20Protection%20Bill%2C%202022_0.pdf

[2] Please refer “Explanatory Note to Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022”. Available here: https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Explanatory%20Note-%20The%20Digital%20Personal%20Data%20Protection%20Bill%2C%202022_0.pdf

[3] Available here: https://www.meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Notice%20-%20Public%20Consultation%20on%20DPDP%202022.pdf

[4] Clause 1(2) of the 2022 Bill.

[5] Clause 2(13) of the 2022 Bill defines personal data as “any data about an individual who is identifiable by or in relation to such data.”

[6] Clause 4(1) of the 2022 Bill.

[7] Clause 2(6) of the 2022 Bill defines Data Principal as “the individual to whom the personal data relates and where such individual is a child includes the parents or lawful guardian of such a child.”

[8] Clause 18(1)(d) of the 2022 Bill.

[9] Clause 4(2) of the 2022 Bill.

[10] Clause 2(1) of the 2022 Bill defines automated to mean “any digital process capable of operating automatically in response to instructions given or otherwise for the purpose of processing data.”

[11] Clause 2(16) of the 2022 Bill defines processing as “processing” in relation to personal data means an automated operation or set of operations performed on digital personal data, and may include operations such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation, alteration, retrieval, use, alignment or combination, indexing, sharing, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, restriction, erasure or destruction.”

[12] Clause 4(3) of the 2022 Bill.

[13] Clause 7(8) of the 2022 Bill.

[14] Clause 7(5) of the 2022 Bill.

[15] Clause 7(6) and 7(7) of the 2022 Bill.

[16] Clause 8 of the 2022 Bill.

[17] Clause 17 of the 2022 Bill.

[18] Clause 23 of the 2022 Bill.

[19] Clause 2(14) of the 2022 Bill.